|

|||

|

| |||

Winning the battle against poverty and disability

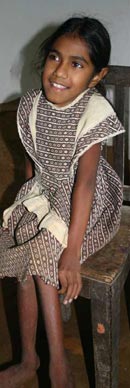

Disability, whether mental or physical, does not disable a person. Discrimination, social stigma and poverty does. A very vocal group of participants gathered at a Colombo hotel recently to find ways of breaking these vicious links to disability, thereby paving the way for Sri Lanka's growing number of differently - abled persons to be part of the mainstream of society. The occasion was a three day National Workshop, sponsored by the Asian Development Bank and Social Services Ministry, opened by Minister of Social Welfare Ravindra Samaraweera, to review the Asian Development Bank's Regional Technical Assistance Project on Disability and Poverty Reduction in which concerns and issues related to both disability and poverty took the centre stage. The participants who included a wide cross section of representatives from both the government and non government sectors, raised a number of significant issues which marginalised persons with disabilities and prevented them from fully participating in society they lived. Their observations and suggestions which were eye openers in more ways than one, revealed a number of disturbing trends and facts relating to disabled persons not only in Sri Lanka but in the region as a whole. For example, with relation to the extent of poverty both on a global scale and at a national level, a synopsis of a background paper by the ADB for its new poverty reduction strategy disclosed the tragic truth that as many as 900 million people in the region (one out of three Asians) live below the poverty line - on less than one dollar a day! Participants also learned that out of Sri Lanka's current population of approximately 20 million, one fifth (i.e. 3-4 million) fell into the category of "poor" or "poorest of the poor" - and that their plight (including the disabled) was exacerbated by the prolonged civil conflict in the North and East. This fact has been underlined in the recent WHO report which has drawn particular attention to the poor health of the women and children in the North and East, prompting the Health Ministry to rush emergency aid kits to affected poor families. However, the lack of a comprehensive data base of information on the extent of poverty of disabled persons emphasises their marginalised and invisible status. Discussions also focused on the question of how poverty and disability should be defined. In this context it is interesting to see how poverty was defined in our country. The Department of Census and Statistics came up with the following definition when it undertook to conduct a Household Income and Expenditure survey in 1995/96. It laid down two conditions for categorising a household as 'poor': namely, households belonging to lowest for per capita expenditure and households which spend more than 50 percent on their household expenditure on food. The households which fell into these two categories were defined as "poor households". Based on these poverty indicators, the Survey revealed some disturbing facts about the extent of poverty in this country. It showed that 26.7 percent of households in Sri Lanka belong to the lowest rung of society. The highest percentage of poor families (47.7%) live in the Moneragala district and the lowest number (9%) reside in Colombo. The same survey further revealed that the extent of the average adult equivalent energy consumption per day for these poor households was 2011 kilocalories per adult per day. A surprising disclosure was that the poor in the Western province had the lowest average per adult equivalent energy consumption for poor households, and thus fell into the category of the "poorest of the poor". Ms. Mallika Ganasinghe's background paper identifying Disability Issues in relation to poverty reduction was equally thought provoking. Citing UN figures she pointed out that on the global scale, one person in twenty suffered from a disability, with more than three out of four living in poor developing countries. These statistics clearly established a visible link between poverty and disability. She also observed that in Sri Lanka, an estimated 5-8% i.e. around 900,000 to 1.4 million of the population suffered from some form of disability, and was estimated to increase "drastically" within the next decade. Members of the medical profession attending the workshop endorsed this view while demonstrating how poverty has a direct and adverse effect especially on the health of women and children. Disability was seen as the outcome of malnutrition resulting from poverty. It was observed that poor malnourished mothers usually give birth to low weight babies who in turn often grew up to be stunted and retarded mentally and physically. Ganasinghe quoted a UNICEF/government study in 1991 that 47% of disabled persons in this country were under 14 years of age - a tragic fall-out of poverty. A 1995 study by UNESCO has underlined this fact, stating that malnutrition in mothers and children was one of the commonest reasons for impairment, with over 20 percent of persons suffering from some form of disability worldwide. To counteract the spread of disabling diseases caused by poverty, the WHO is currently intensifying action against what it calls "diseases of the poor" especially against three diseases associated with poverty - HIV/AIDS, T.B. and Malaria, the target population being mainly poor women and children who are more likely to suffer from disabilities as a result of such diseases than the rest of the population. Discussing the causes for disability it was noted that accidents, war related psychological trauma which mentally scarred the victims for life; infectious diseases, congenital diseases and ageing which led to mental diseases such as dementia, were among the most common reasons for impairments among young and old. Reflecting on the constraints that prevented disabled persons from enjoy equalling opportunities, participants spelt out a number of gaps in the current services available to such persons in this country. The lack of awareness of the rights and needs of disabled persons by society in general, lack of education, medical care, rehabilitation services and support services, education, skills training and employment were listed as some of the biggest constraints. So how could such constraints be overcome or eliminated? It was stressed that initially a change of attitude was necessary by society as a whole to remove the stigma and prejudice against such persons. Ms. Ganasinghe cited the following case to show how even the law tended to favour the able as against the disabled. In 1992, she said, the UN Human Rights Commission identified a case in Germany where a group of disabled persons staying in a hotel were charged by a group of able persons on vacation in the same hotel, for disrupting their holiday. Their crime? "Because you are ugly and upsetting us". The unexpected finale to this shocking incident was that the court ruled in favour of the plaintiff and ordered the group of disabled persons to pay them compensation! It is in this context that awareness of the Human Rights of disabled persons by society as a whole played an important role. The question was raised as to the extent of awareness of these rights in Lankan society, and what efforts have been made collectively and individually to integrate the differently abled in the mainstream of society. Referring to the Rights of disabled persons in Sri Lanka, and the services provided for them, it was revealed that disabled persons were protected by the Constitution in which their rights were enshrined( Act no 26 of 1996). Yet, the shocking truth was that less than one per cent of persons with disabilities had access to health, education, social services, while the majority of disabled children were deprived of education altogether with few of them never receiving any skills training for employment purposes. Another disturbing fact that emerged from the discussions was the negative attitude that most employers had towards the disabled. This too was identified as an significant barrier to their mainstreaming. Lack of authority to enforce this Act in relation to employment as well as accessibility (lack of ramps and special provisions to facilitate entering buildings etc) was identified as one of the biggest constraints." As such the Act has been used more as a policy document rather than legislation", Ganasinghe noted. It was also noted that disability has never been an issue included in any political agenda although disabled persons too had the right to vote. On the plus side, participants were also briefed about the positive steps that had been taken in recent times towards empowering the disabled in Sri Lanka. One such was the increased awareness of the needs and rights of disabled persons - the result of collective efforts by parents, teachers, NGOs and various government ministries including the Social Services Department. In addition to this awareness, a number of new services have been introduced for the benefit of disabled persons. They included; the establishment of a National Council, National Secretariat and the registration of organisations working with and for persons with disabilities. Provision for financial aid to disabled persons to build houses is another recently introduced new service. A serious effort was also being made by the Social Services Ministry and other organisations to provide the disabled with skills training in job oriented fields. Still, in spite of such steps, the consensus of opinion was that there was a long way more to go before the differently - able in Sri Lanka can finally come into their own. It was thus agreed in conclusion that in implementing the Poverty Reduction Technical Assistance Program of the ADB in Sri Lanka, a more holistic approach should be adopted to poverty reduction. Efforts should also be made to clearly identify the links between poverty and disability and see how far issues related to disability could be included in a sustainable development program. Only then would the differently able be able to enjoy a new lease of life. Article by Carol Aloysius courtesy The Sunday Observer of Sunday, 1 September 2002 Other articles:

|